We cover an array of topics here: click on the categories below to focus on your particular interest, or simply read them as we wrote them. We promise no linear narrative here.

homes

case history: cold climate house /

case history: cold climate house

A broken leg strands us in Boston, Massachusetts for the winter, for what turns out to be a 108" spectacle of record breaking snowfall. With a good understanding of tropical and desert architecture, we use the time to ask ourselves what cold climate architecture ought to be about. We think it ought to be a combination of hibernation and celebration, offering snug retreat from the elements, but also offering the opposite: immersion in the outdoors.

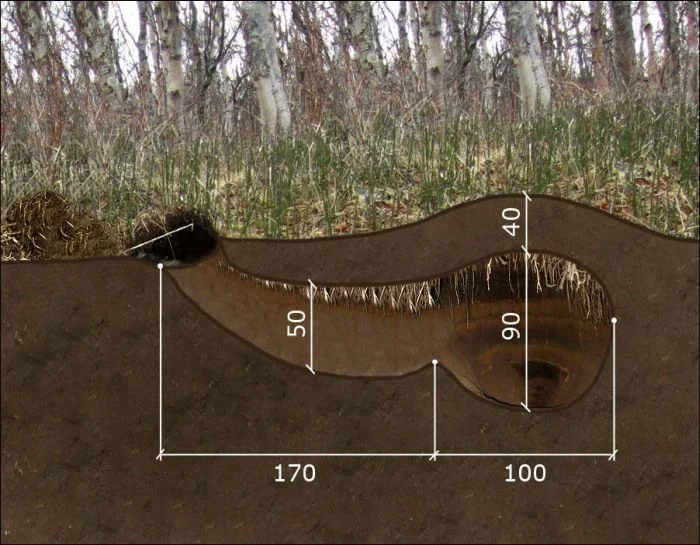

Bear Den

It seems to us, in thinking about designing a house in a cold environment, that we are exploring the territory between a bear den (very cosy and warm, but inwardly focused and both physically and emotionally buffered from the outdoors) and a bird nest (very exposed, but outwardly focused and extraordinarily panoramic).

Bird Nest

Two other references came to us in imagining a house in snow: the igloo and the "A" frame.

Igloo: maximizing volume while minimizing surface area, modular in construction, the interior a simple fire circle: house reduced to heat and shelter.

Igloo

"A" frame: a house reduced to all roof: one big, structurally quite simple, attic. Between Igloo and "A" frame lie clues to a house.

When we design a home, we seek to identify and celebrate the rituals it will host, seeking meaning by orchestrating ritual and context. This is the difference between a dull ceramic sink stuck in a vanity cabinet in a dark bathroom that has you face a small mirror on a blank wall, and a glass sink magically floating on a completely mirrored wall (see our Massachusetts house), or a sink freestanding in a room like a large fountain, facing the Pacific (see our Hawaii house). We can look at the rituals of a house, and begin to imagine contexts for them on the spectrum between den and nest.

What are the rituals of a house? We cook, we eat, we sleep, we work, we relax. In cold climates, fire takes on special significance.

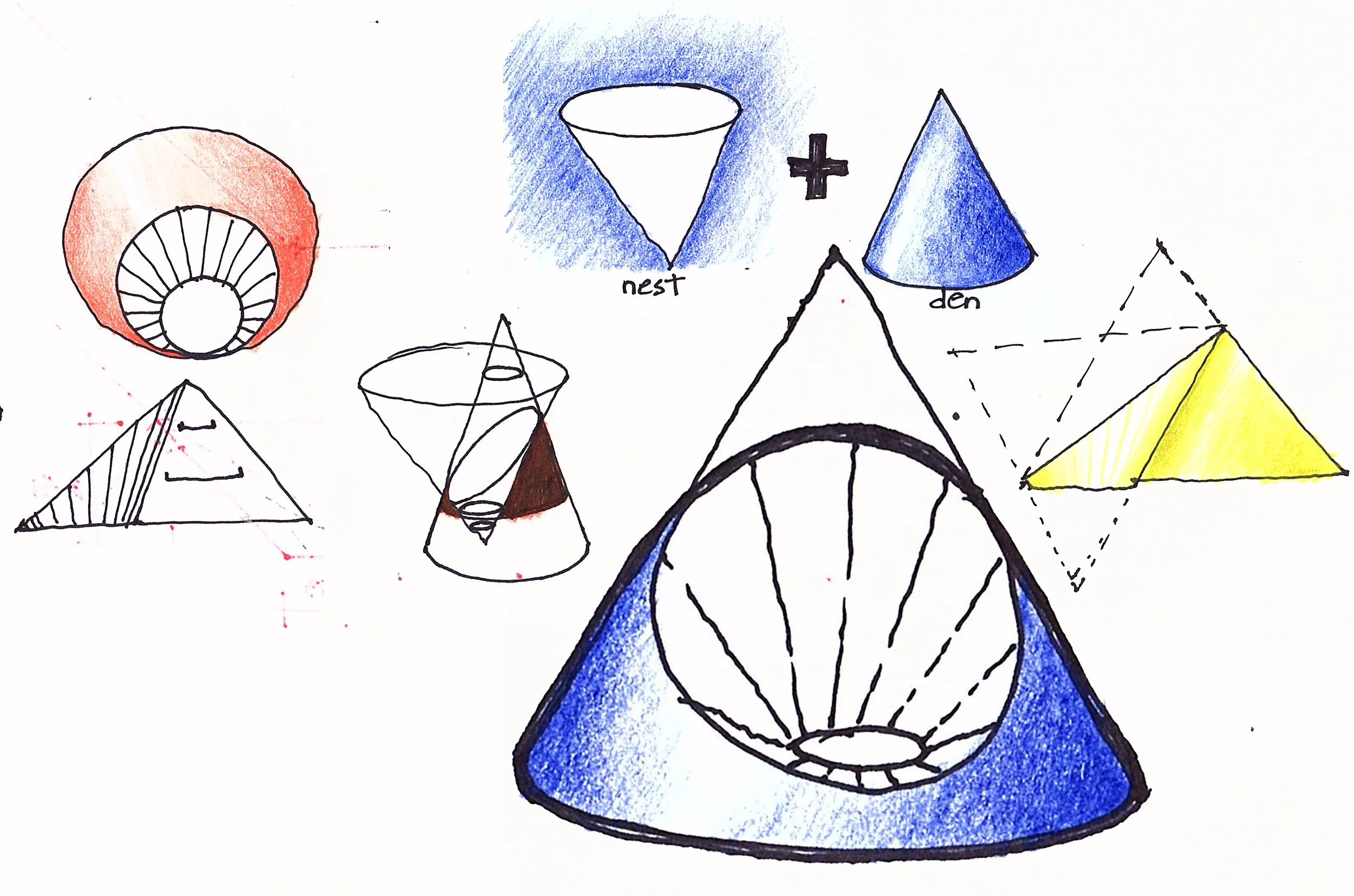

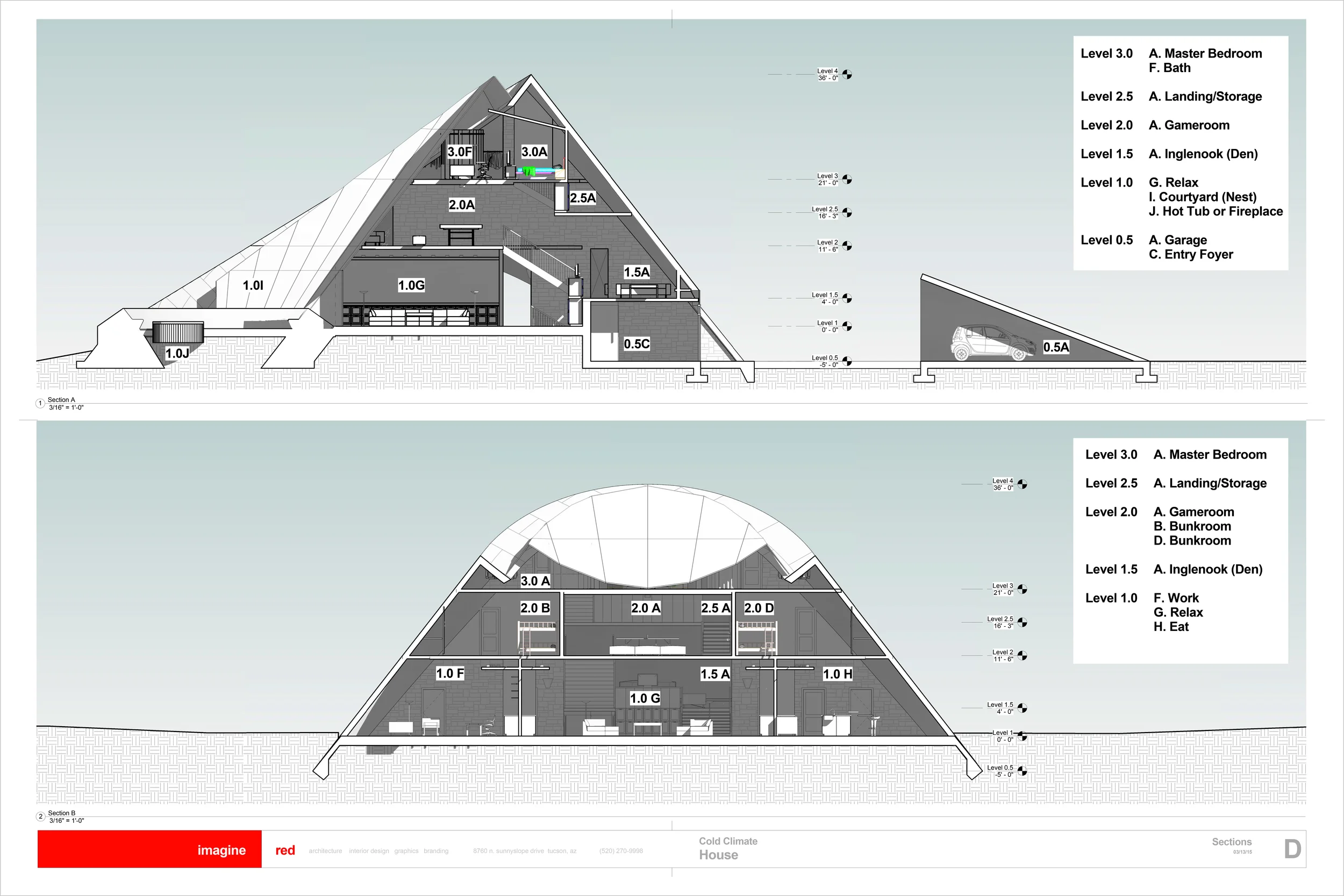

A house offering bear den and bird nest, learning from igloo and "A" frame, celebrating fire while living in ice: this is what we set out to imagine. Den and Nest, Igloo and "A" frame, all got thrown in the soup pot, and out onto our sketchbook came 2 cones superimposed: nest carved out of den, the resulting section an "A" frame curved into a croissant. If that sounds abrupt, we will admit to a few ugly sketches in advance of these ugly sketches, and also a growing sense that simply stacking rectangles can't be the only sensible answer to most design problems, and also some curiosity about the problems that would ensue from heading down this path.

Of course, it's a long road from concept to construction. This little idea, however, seemed to have both the relative simplicity and the emotional content to survive the journey. While our design in desert and tropical climates had always been more organic, with the edges deliberately blurred, it seemed entirely appropriate in extreme cold to be very precise about our envelope, while still embracing a small piece of the outdoors. It was a new way of working for us: from the outside in.

The house spends a lot of time on our computers, changing, stretching...

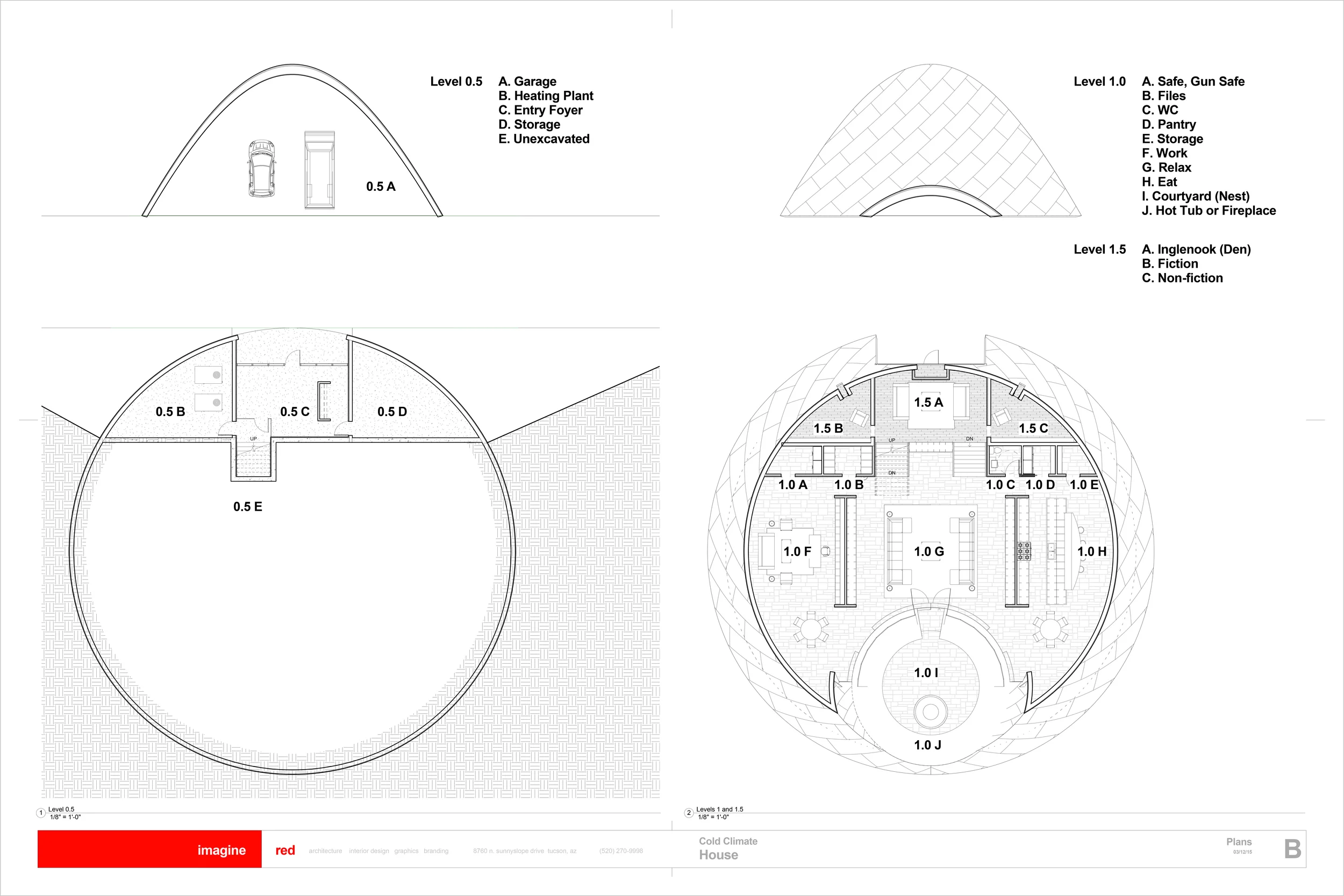

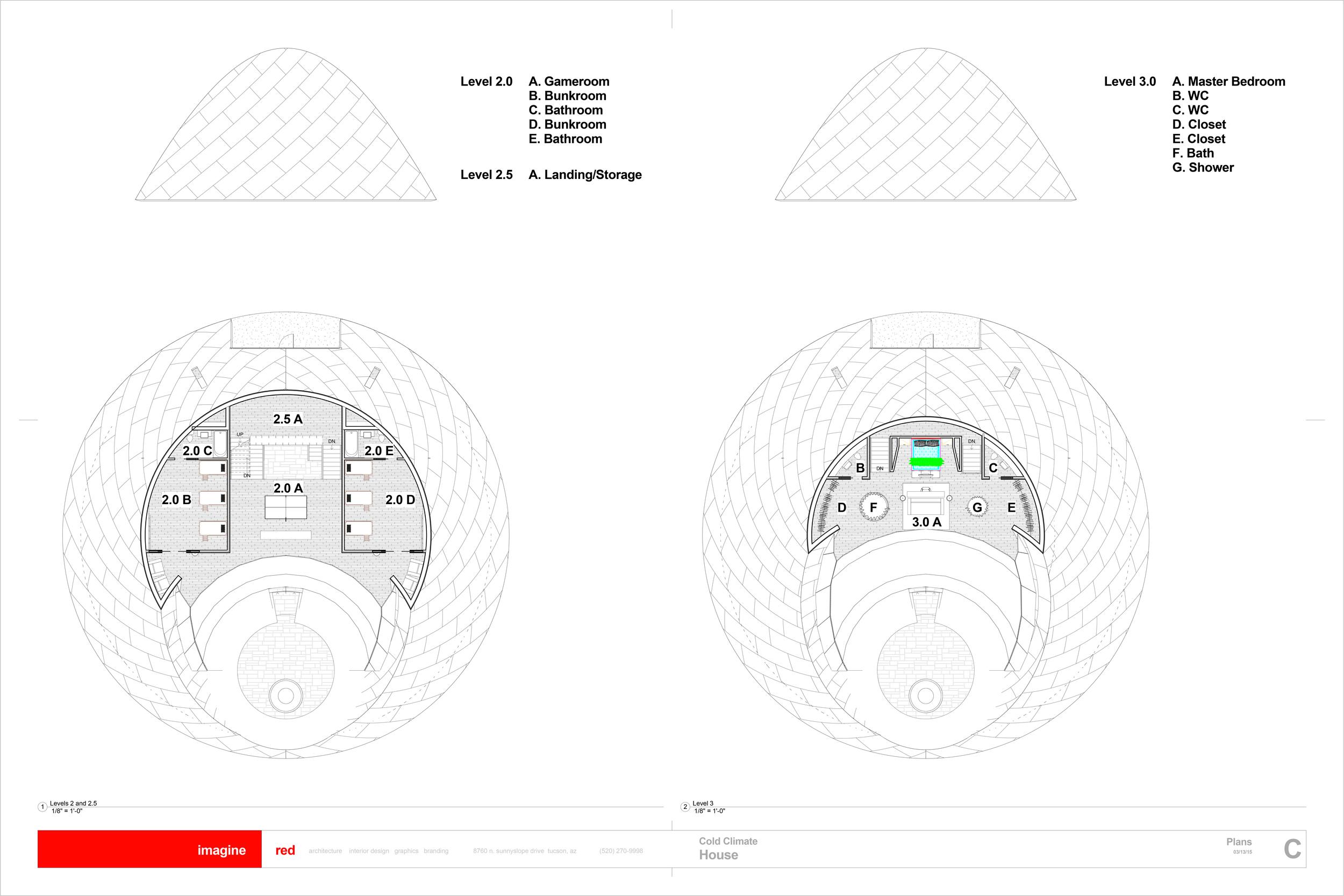

Here is a house that came out of it:

Both cave and nest, inglenook and courtyard, focus on fire as an important part of the experience. Despite the triple glazing and the southern orientation and the stone floors to absorb heat and moderate internal temperatures and window blankets to minimize nighttime heat loss, it will be interesting to see how much courtyard glazing survives design development should the project go any further. We would add a canopy over the front door and work on the bunkrooms some more as well, so that they too could partake of the view. To lie in bed every night and stare up at the sky: that would be worth the additional effort.

case history: the desert home /

case history: the desert home

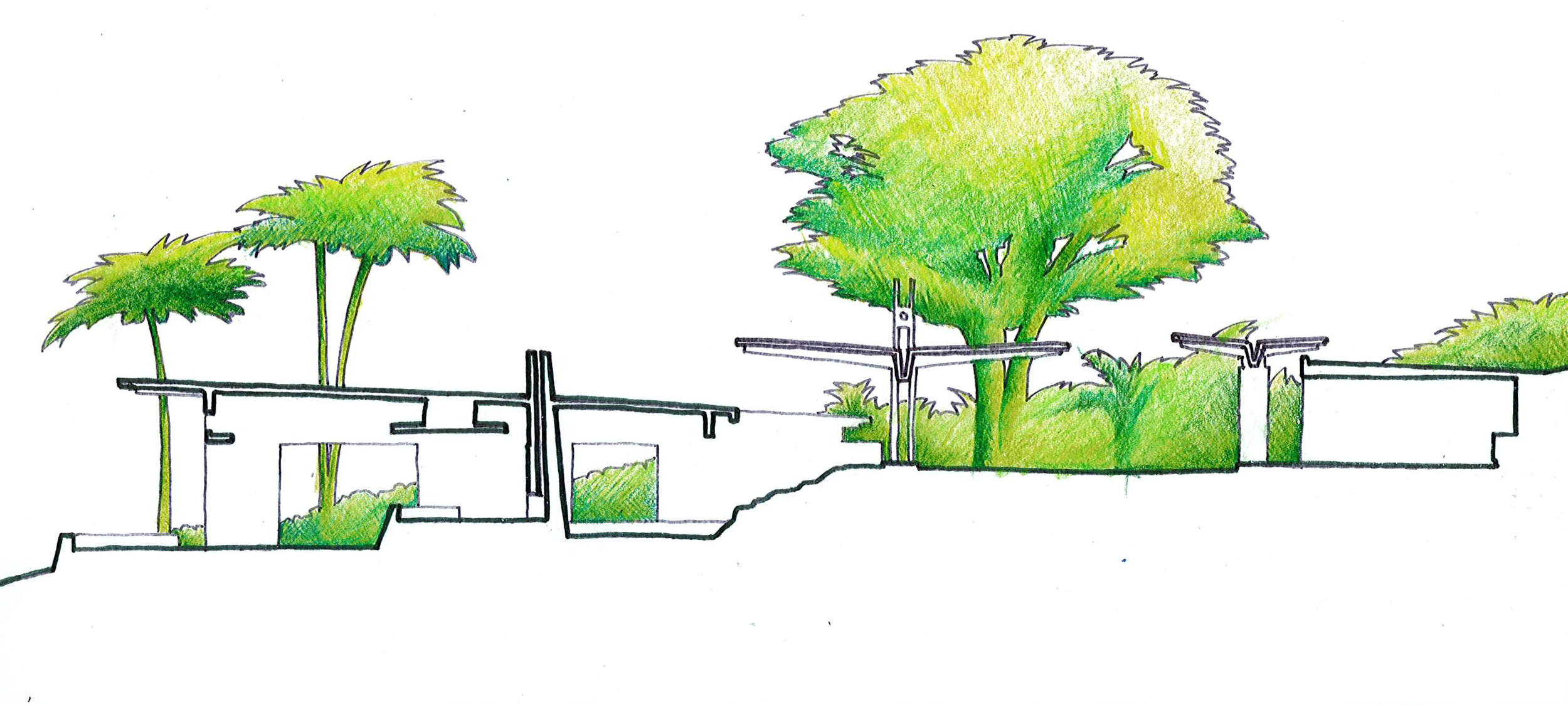

Our ideas about building in the desert come from three months spent crossing the Sahara Desert in 2006, and from 6 years now in the Sonoran Desert of Arizona. From the Sahara, we got a visceral sense of the difference between building with earth and building with concrete. The bottom line was this: In the absence especially of large quantities of expensive insulation, earthen construction was almost always comfortable, and concrete construction rarely so. In the Sonoran Desert, we've come to draw inspiration from the creatures that operate comfortably in the environment, and extract typologies from that examination. The house discussed here draws from the Desert Tortoise, relying on a tough, insulating shell to shield the more vulnerable living space within.

...a face only his mother could love...